A professor of palliative care and member of the House of Lords has stressed that extensive studies show no medical prognosis can be considered definitive. A prognosis refers to a doctor’s estimate of how long a patient is expected to live with a particular illness.

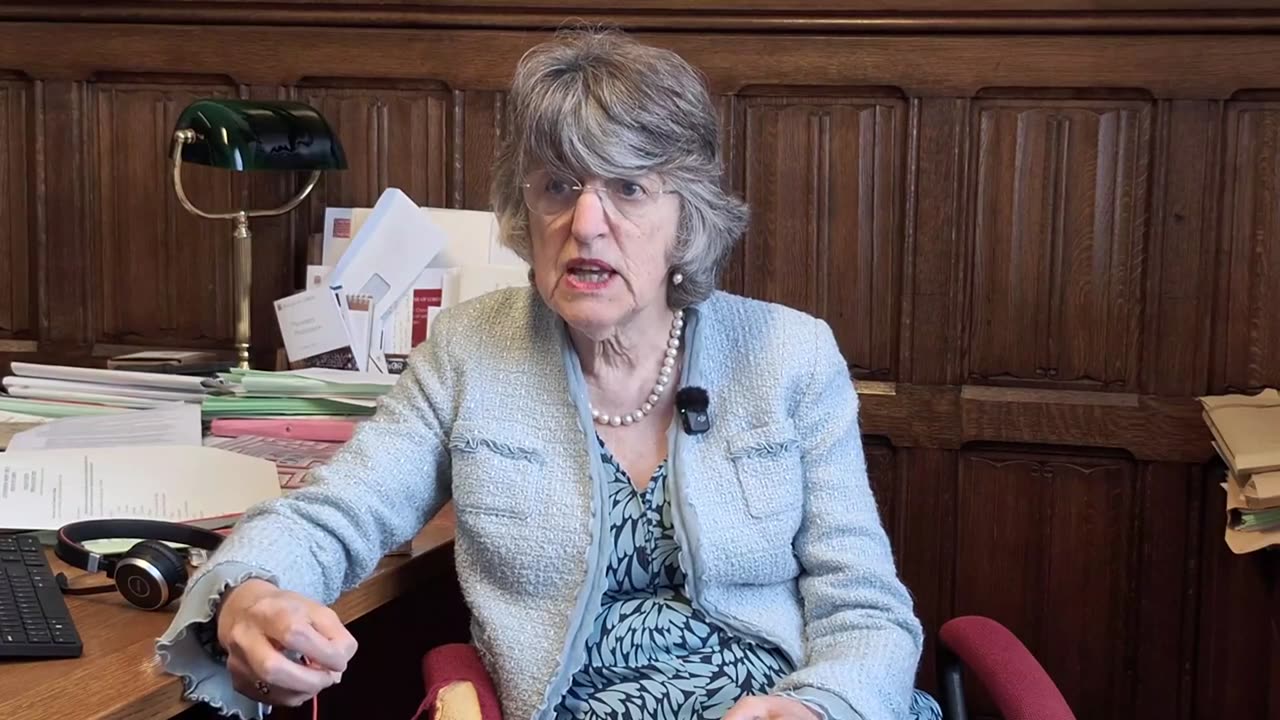

In an interview with Newsbook Malta at the Palace of Westminster in London, Professor Ilora Finlay recounted how, around 30 years ago, she and three other doctors predicted that one of their patients had only three months to live.

“I was speaking to him on the phone last week. He’s still alive,” she said with a faint smile.

As the government’s public consultation on assisted voluntary euthanasia enters its final week, Prof Finlay emphasised the conditions that must be met before one can make such a decision: the individual must be fully informed, mentally capable, and the decision must be entirely voluntary.

The White Paper currently under consultation proposes that terminally ill patients with less than six months to live be granted access to medication that would allow them to end their lives voluntarily. While the government has not yet committed to introducing legislation, the proposal has met strong opposition — particularly from the Catholic Church, which rejects euthanasia on moral grounds and advocates for improved palliative care instead.

On the question of being properly informed, Prof Finlay noted that one in twenty people was found, after death, to have died of something other than the illness for which they were being treated — highlighting the fallibility of medical diagnoses.

She was equally critical of relying on prognoses to justify euthanasia. “You simply cannot say how long someone has left to live,” she insisted.

On the issue of mental capacity, Prof Finlay explained that sound mental health is essential when making any major decision — especially one as grave as ending one’s life. Sadly, she said, not all patients are in a position to make such a decision clearly, due to various emotional pressures or the effects of medication.

She also pointed out that one in five terminally ill patients suffers from depression — a factor she believes must be addressed before any such decision is made.

That is precisely why she is wary of rhetoric that promotes this as a purely personal choice, Finlay said, adding that other problems must be addressed first.

Prof Finlay also expressed deep concern about the voluntariness of such decisions, noting that she has witnessed several cases where patients were pressured — often subtly — by those around them. She cited instances where family members complained about the cost of care or expressed interest in the patient’s inheritance.

It is incredibly difficult to determine whether someone is being pressured to choose euthanasia. In those cases, the choice is no longer truly voluntary, she warned.

This critique challenges a clause in the government’s consultation paper, which states that anyone who exerts pressure on a patient to opt for voluntary euthanasia would be committing a criminal offence punishable by imprisonment.

Prof Finlay questioned the practicality of this safeguard. “How can I know that pressure was exerted if the patient is now dead?” she asked. She also explained that, as a medical professional, she is neither equipped nor permitted to investigate such matters, which she believes belong in the remit of the courts — not in the clinic.

Source: Newsbook.com.mt